Selected Works

Teruo Iyama (b. 1919 – d. 2007)

Wrought with uncertainty and interruption, and punctuated by World War II, Teruo Iyama’s childhood and early life included movement between California and Japan, confinement inside Internment Camps and even renunciation of his US Citizenship1. Despite being forced to leave his education at The California School of Fine Arts in Oakland behind (and all his artwork2) for the barbed wire desolation of Tule Lake3, Teruo met his eventual wife of over 60 years, Michiko; taught art in the camp as a teacher for Chiura Obata; and welcomed a baby girl into the world in 1945. When the war ended, Teruo and his entire family (including his parents and grandparents) were only given $25 total for their return to normal civilian life. Through hard work, discipline and focus, Teruo established a successful nursery and landscape design business in Sausalito and eventually retired young—a testament to a positive and happy man who always had a smile on his face.

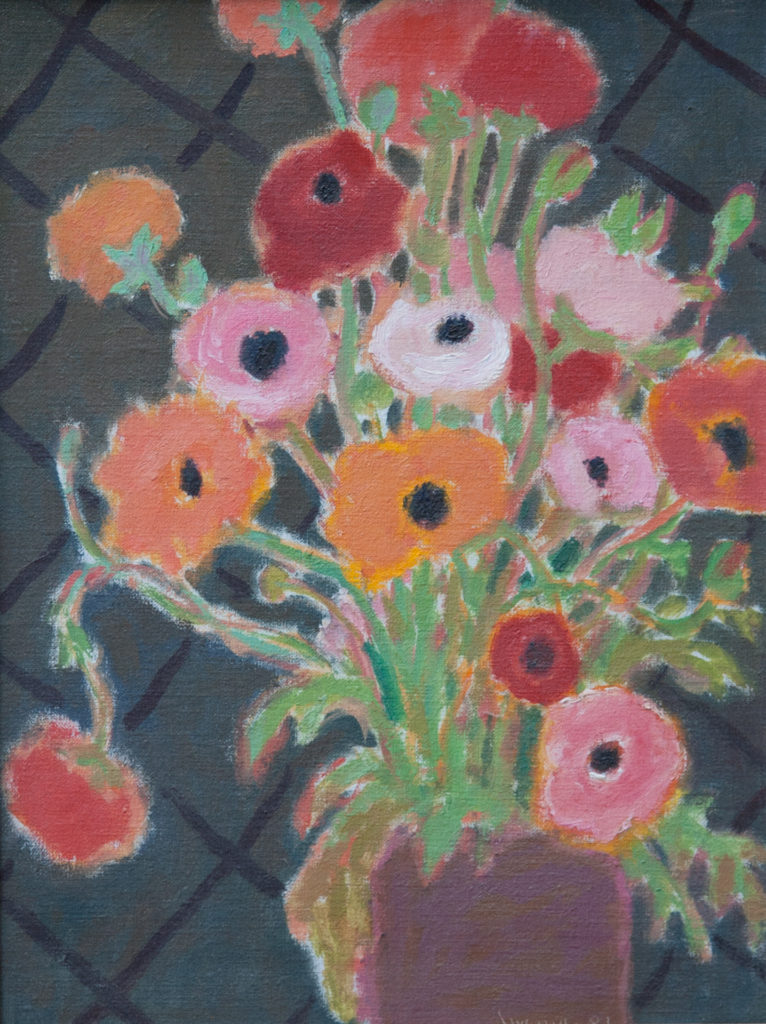

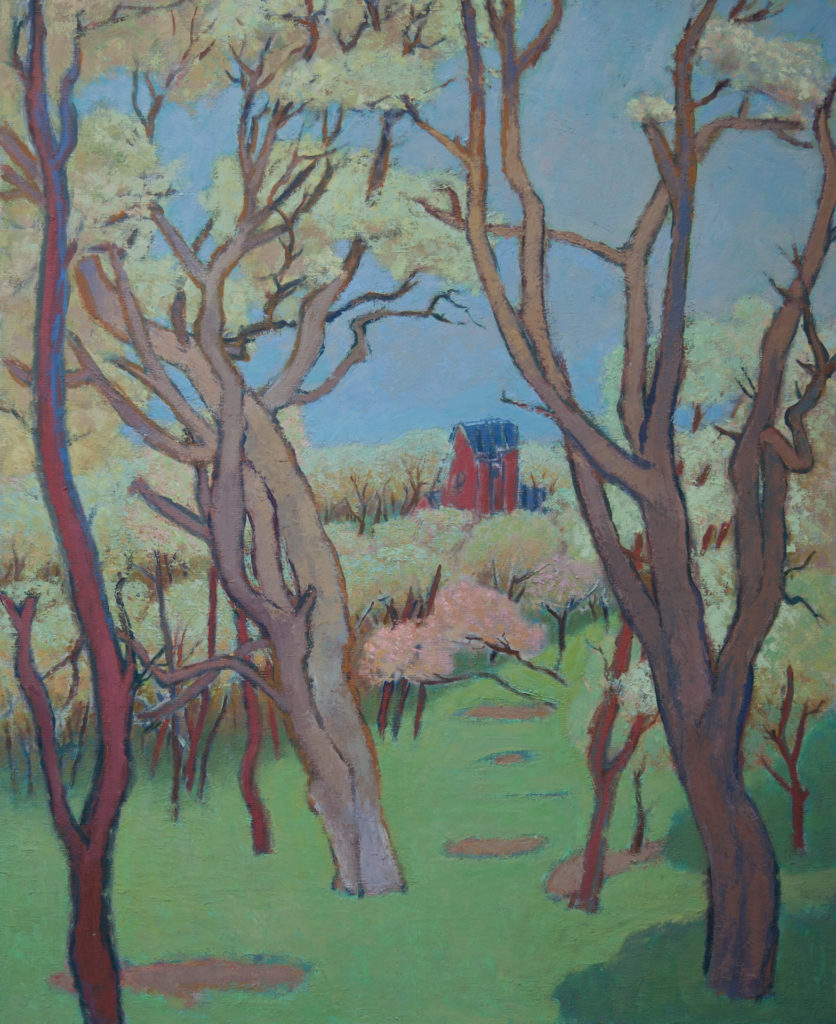

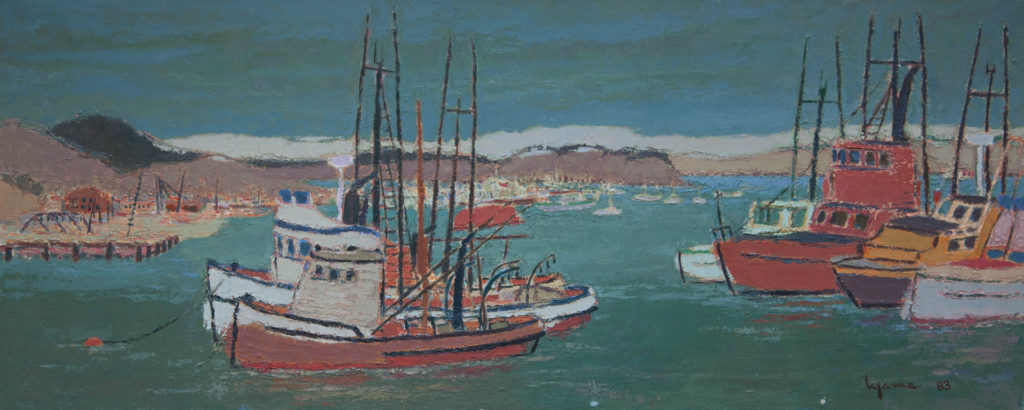

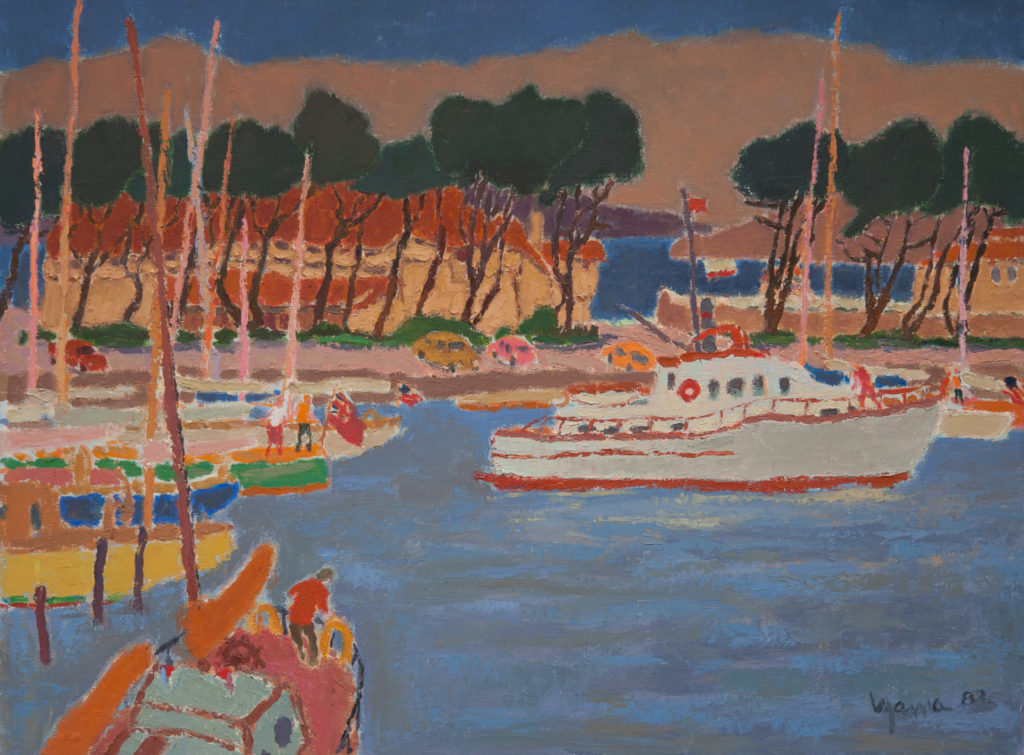

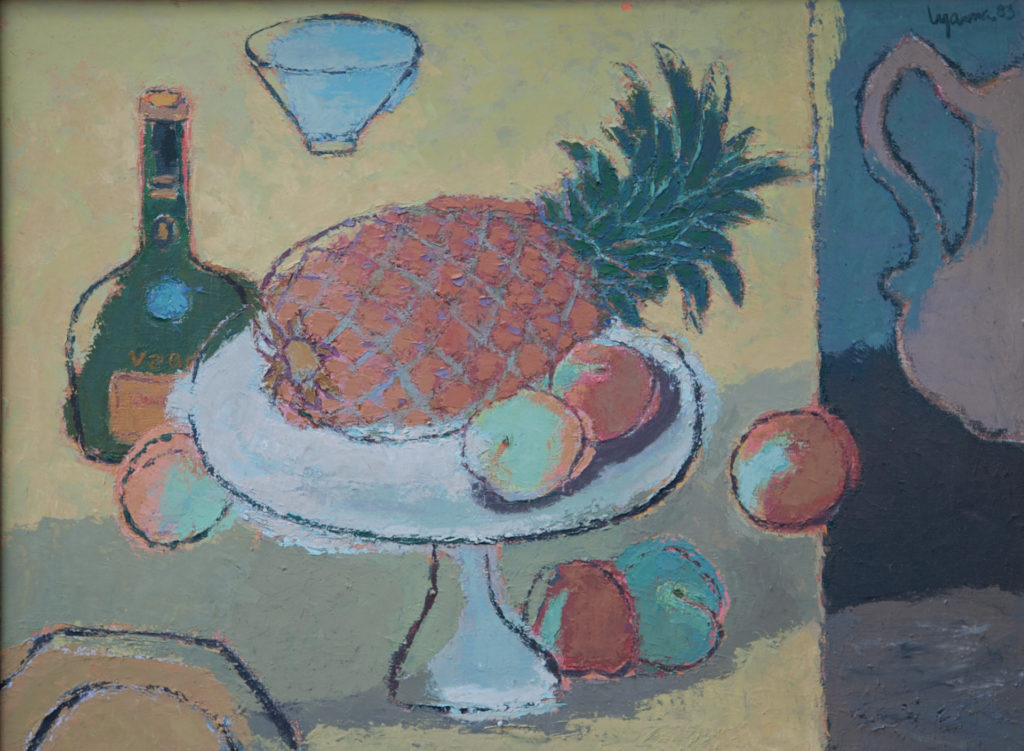

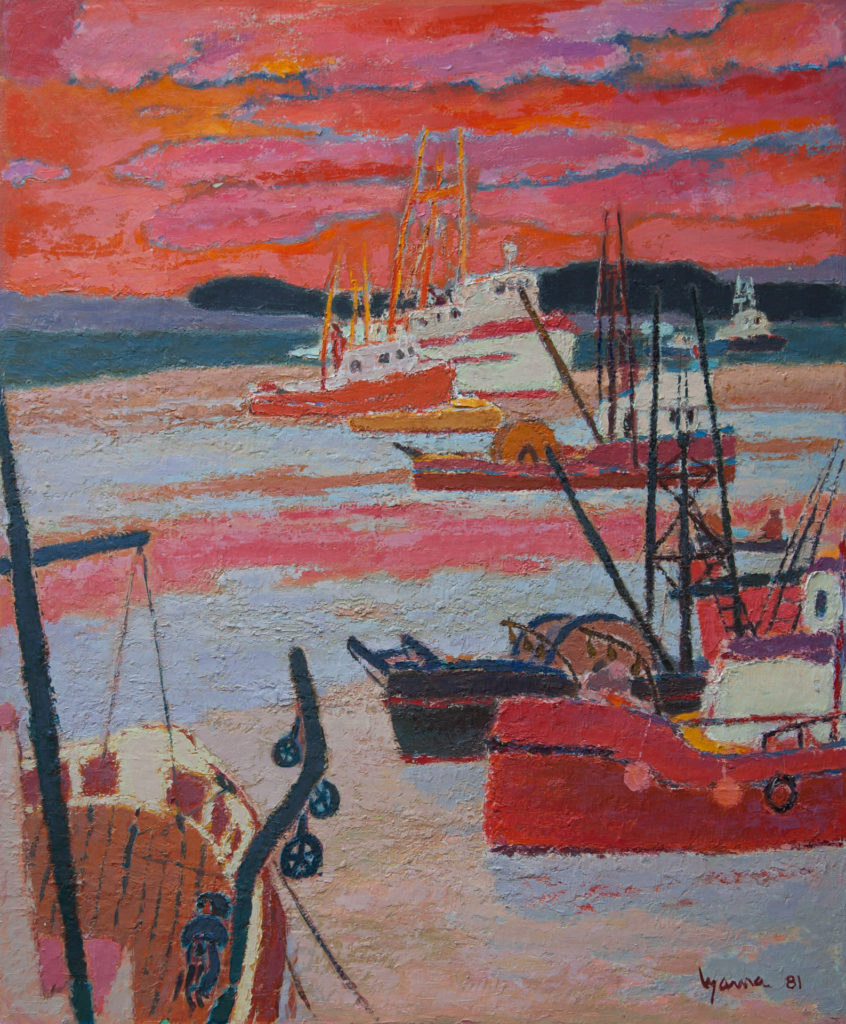

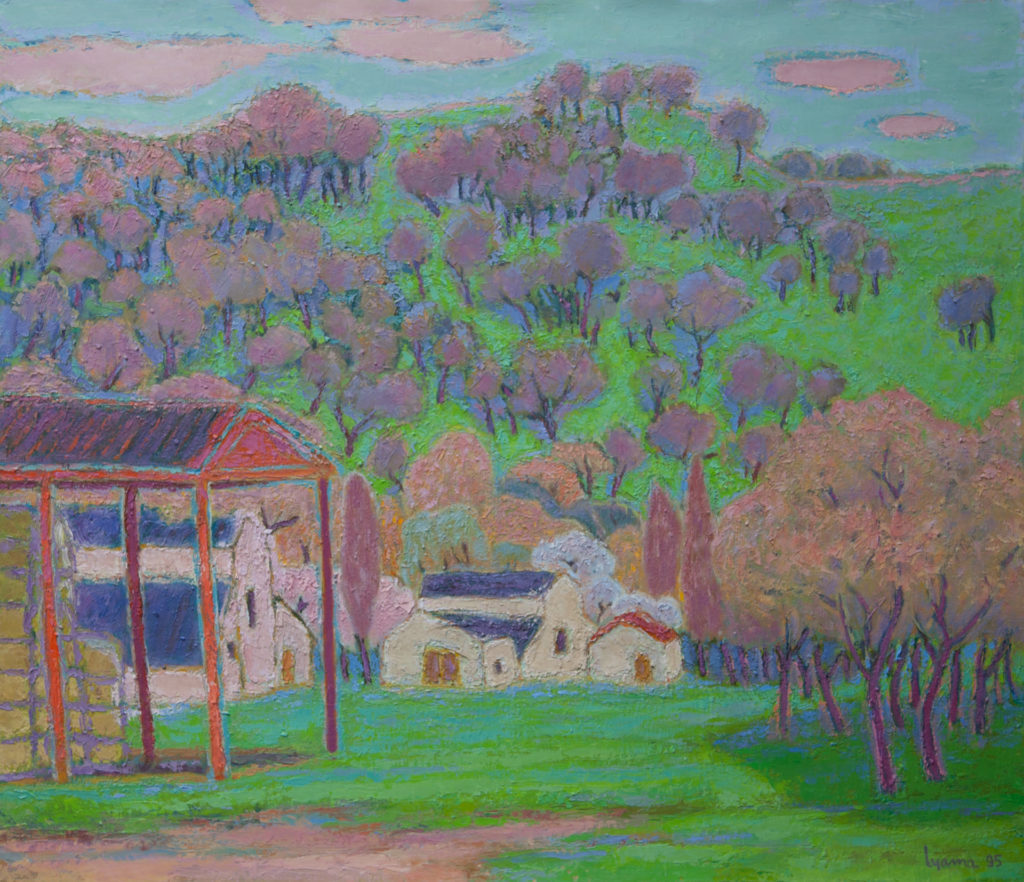

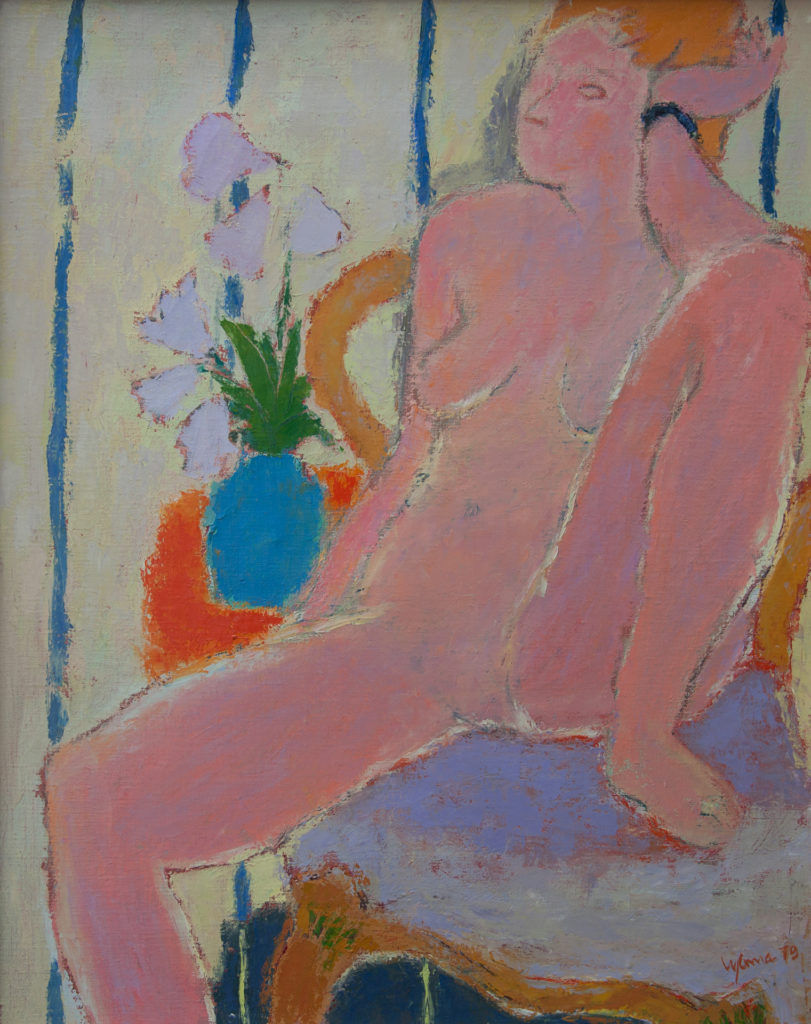

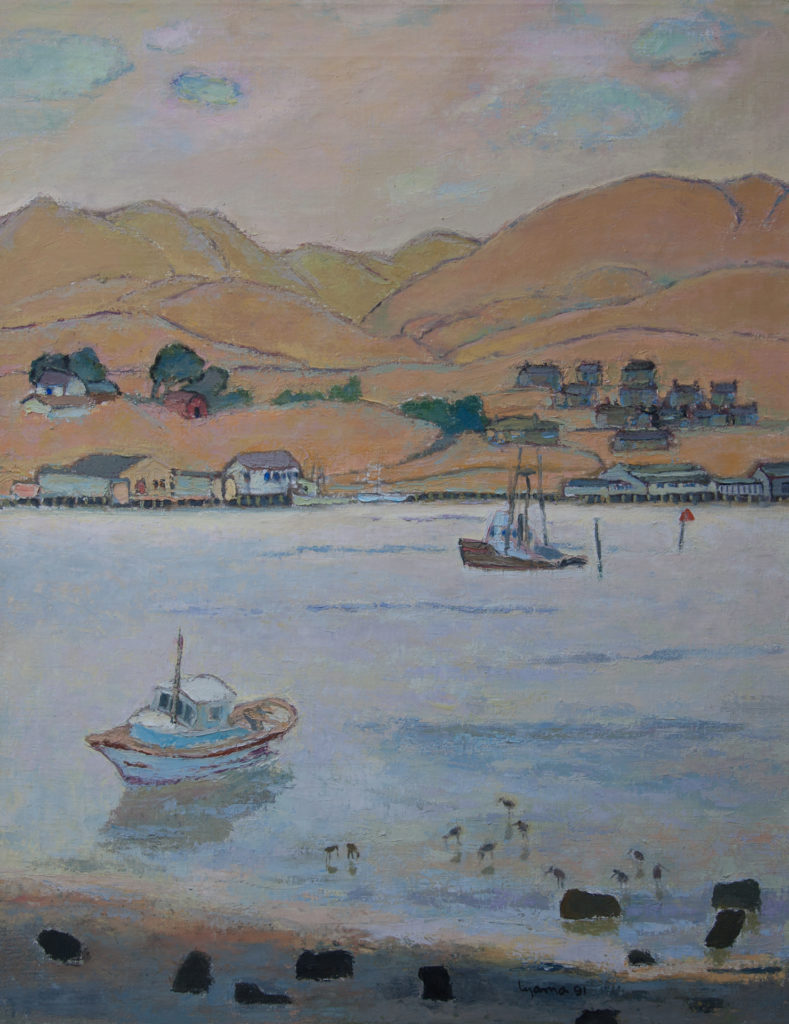

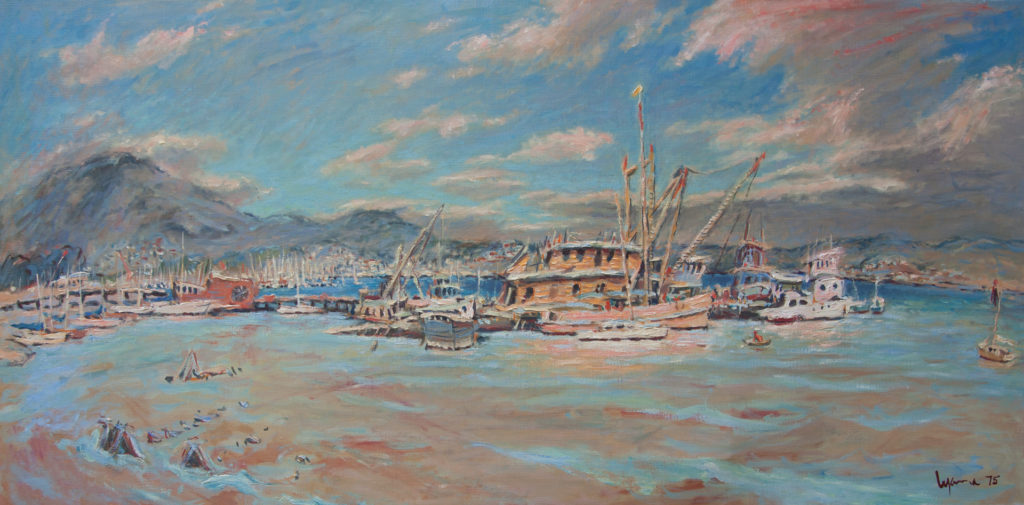

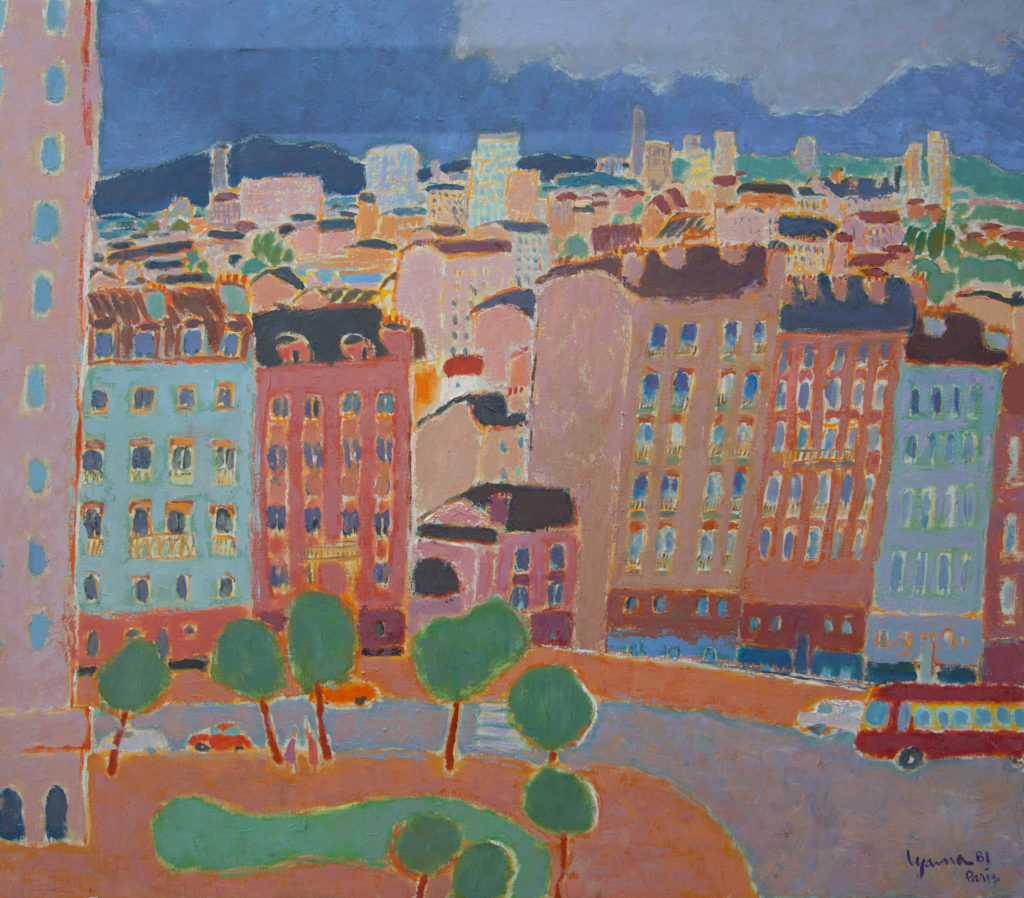

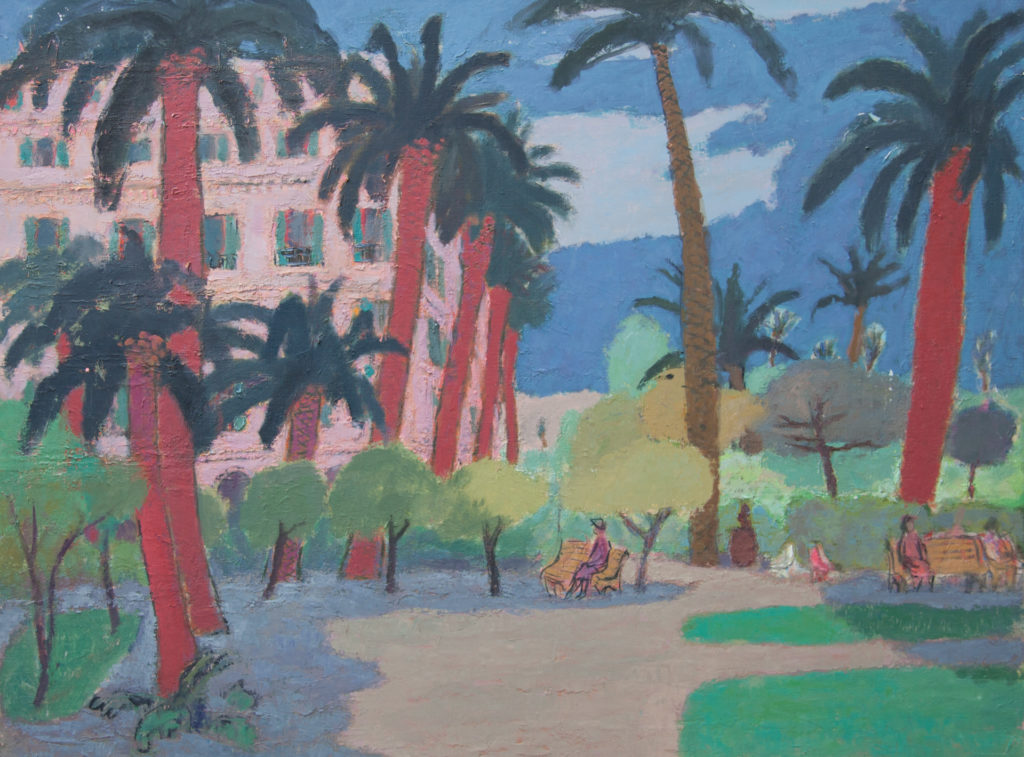

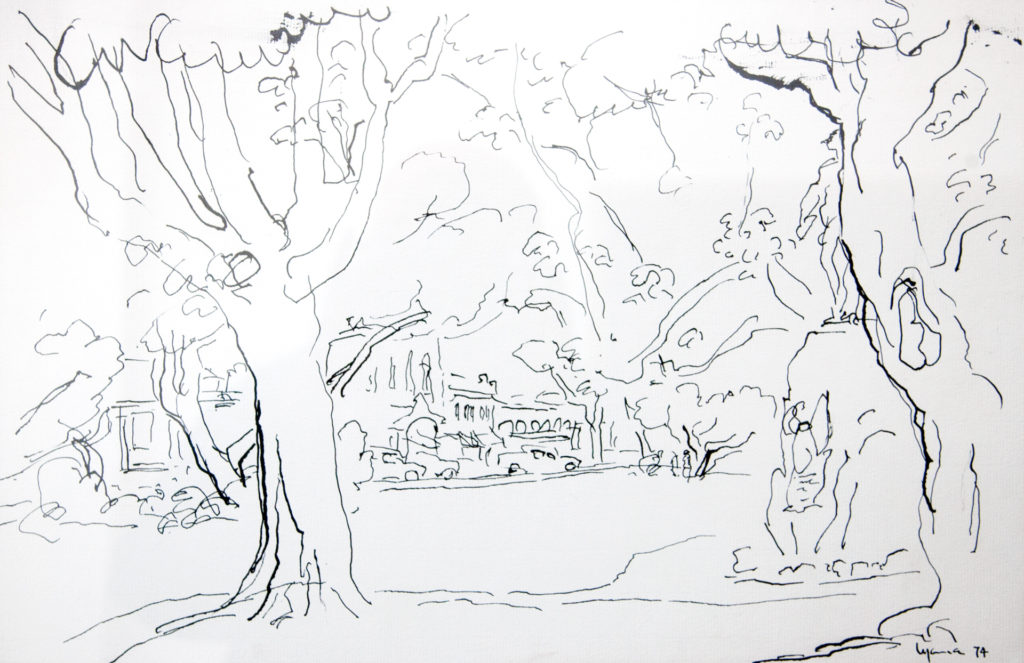

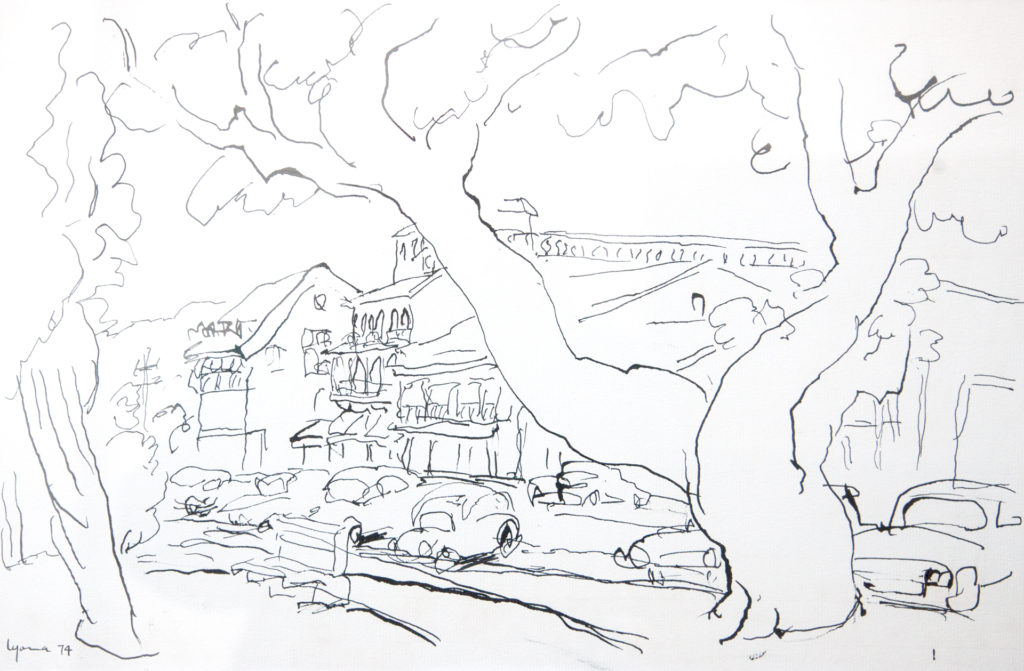

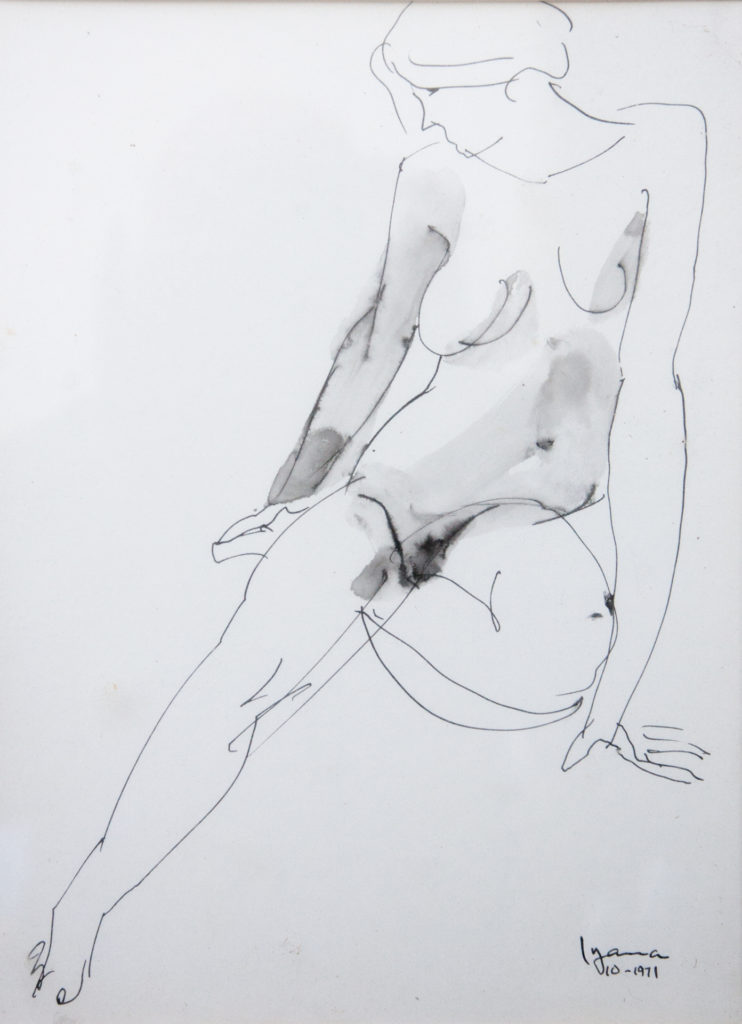

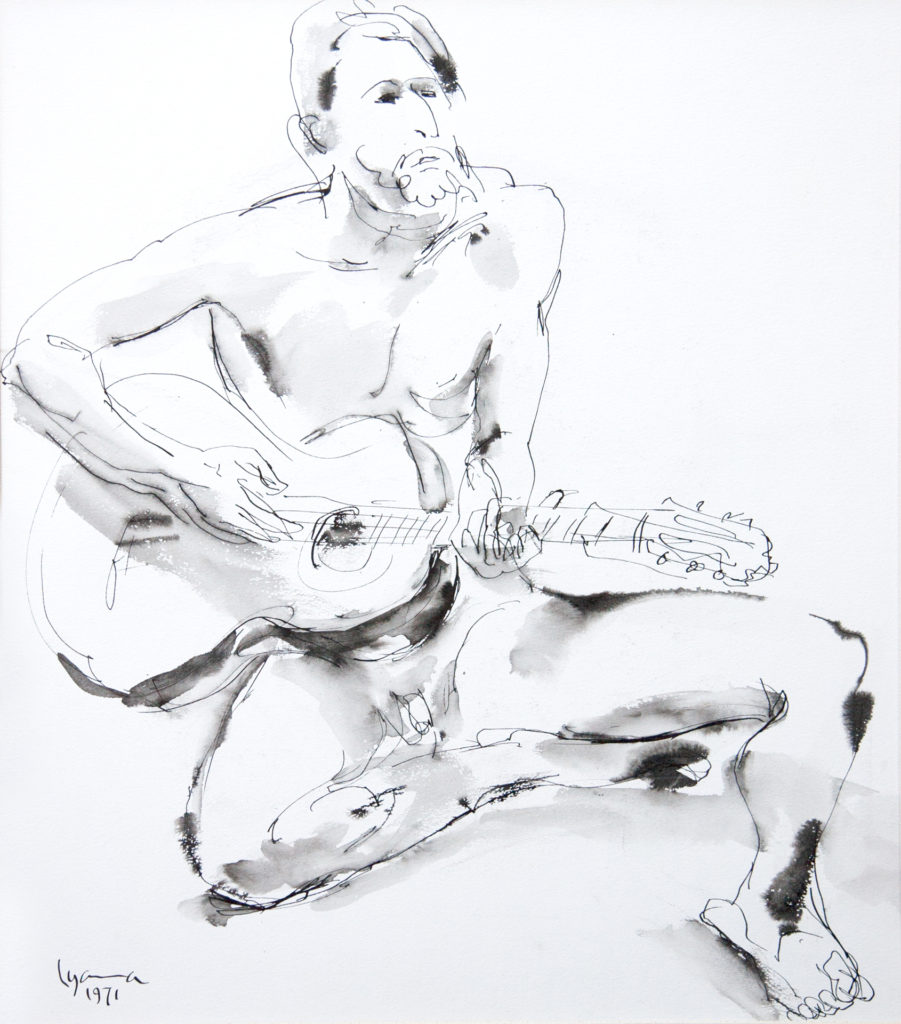

Wherever Teruo went and whatever Teruo did, he always loved to create; he maintained an exquisite home garden, built custom homes and furniture, fabricated beautiful stained glass windows and lamps, sewed designer clothing and painted stunning oil paintings in the bright, light style of the Impressionists. His paintings centered around the Sonoma County countryside (landscapes and seascapes particularly featuring boats), city scenes in Europe and still lifes of flowers picked from his garden.

Teruo Iyama is extensively collected privately and has shown his work in the Maxwell Gallery in San Francisco and the Swanson Gallery in Sausalito.

Teruo Iyama was born in Berkeley, California to Kwango Iyama and Asao Ishii. He passed away in St. George, Utah as an American citizen; at that time, he was survived by his wife, daughter and two grandsons.

1 Teruo Iyama refused to answer the “loyalty questions” (#27 & #28) of the War Relocation Authority’s Loyalty Questionnaire. As an American Citizen, he was deeply offended by questions of his loyalty. That combined with the treatment he and his family received, led Teruo to renounce his citizenship after the war ended.

2 As with nearly every other interned Japanese and Japanese American, Teruo Iyama was forced to give up nearly all his possessions during relocation, including all of his artwork. Teruo refused to pick up a paintbrush until 1975! With all the anti-Japanese sentiment remaining after the war, Teruo felt no one would want to buy his art, and so he waited 30 years.

3 Tule Lake was considered the worst internment camp by virtue of its inclement conditions and location. Troublemakers in other camps as well as those who refused to answer the Loyalty Questionnaire were sent to Tule Lake.